Gardeners (assuming they are not sight-impaired!) need an attentive gaze. Let’s face it, if a garden is going to be in any way appealing the gardener has to consider colour, shape, height, light and shadow among other things. This means a lot of looking and thinking and planning, all of which can be a balm for the mind in these times of Coronavirus. But gardening is also a powerfully sensuous activity in which touch, although often ignored, is paramount. No gardener is unaware of the feel and texture of rich warm soil, of tough and obstinate roots, of the fragility of petals or delicately pliant leaves.

In the garden I become acutely aware of the thinness of my skin, how easily it is blistered by secateurs, stained by plant juices. And, of course, the sharp stab of a rose thorn is a poignant reminder that these days touch is a dangerous business. We have to maintain distance between ourselves and strangers; we no longer hug friends and relatives. We stare in dismay when others cluster together carelessly. Can gardening – and garden writing – I ask myself, compensate for the lack of physical touch, provide a sort of tactile wisdom, allowing us to feel our way towards a sense of wholeness and flourishing?

If I wander around the garden, brushing my hands over the tops of box hedges my fingers tingle, I feel more vital, and want to explore other touch sensations that are often forgotten in the need to weed, water, prune or generally busy myself with seemingly urgent tasks. Putting these to the back of my mind I immediately become aware of a whole world of touch sensations crying out for attention. Feathery grasses, the velvety lamb’s ears, the tickle of bundles of tiny delicate stamen flowers on the Callistemon, the smooth, leathery leaves of the Japanese laurel. Of course reaching out to grasp plants in the herb garden fills the air with fragrance – rosemary, lavender, dill, fennel, the beautiful citrus aroma of lemon verbena.

So much stimulation brings my attention back to my hands. I look at the skin on my hands – gardener’s hands that have suffered in all sorts of weather so the skin now appears paper-thin, much like the paper I use for my garden diary, although sadly much more wrinkled and blotchy. Today, wet, windy and cold weather sends me back inside to thoughts of paper made from breathing wood, to explore diary entries, neglected books on gardening and tomes of philosophy that have been gathering dust.

Merleau-Ponty (one of my favourite philosophers) argued that the paper and I are of the same flesh. And then there’s Kant who declares that my holding hand is ‘an outer brain’ deeply involved in spatial cognition. With this understanding, we can be open to the world, to the tactile sensation of the garden because we are of the same structure as the world. We are of the same flesh as things and others. Yet, it is astonishingly easy when gardening, writing and reading to forget touch, ignore our hands and concentrate on sight.

When I come inside and sit down to write I feel grounded in the same way as I feel grounded when my fingers enclose the root ball of plant I have lifted from a pot. My holding hand as ‘outer brain’ involves me in space and thought whether writing or digging. These days, when showing visitors around the garden is much less common, I hope writing will create a sort of touch at a distance. After all, narratives affect us, change us, touch us literally and metaphorically.

My garden diary is a messy affair – much like my garden. I have friends who are supremely organised and have all their plants on spread sheets. Not so me. My diary is paper-based as I like to add drawings, sketch and scribble as well as write.

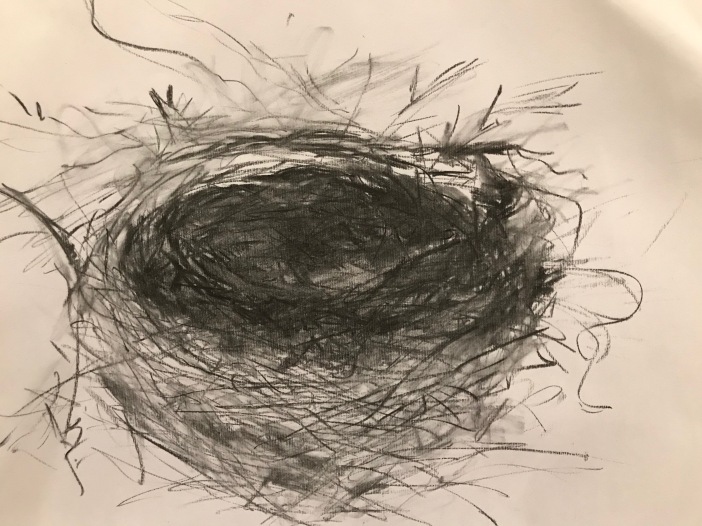

There’s the turnips ready to add to lentil soup for lunch. There’s a little nest exposed when the Maple shed its leaves.

And there’s a portrait of Blossom, the silver-laced Wyandotte who likes nothing better than bossing the other hens around. Much of the writing is merely disconnected phrases that come into my mind while outside – oddments I imagine might find a place in an essay some day.

It’s true that looking, writing and drawing can collapse our three-dimensional lived and embodied knowledge into two-dimensional paper-based (or computer) inscriptions. To forget touch and other bodily senses can leave us stranded in abstractions; the garden can become relegated to a shadow and when nature is no longer felt as a palpable presence it becomes open to exploitation and maltreatment. It is therefore in these times important not to let ourselves feel that the world outside is a dangerous place but one which we must all attempt to nurture back to health.

Famously in his ‘First meditation’ Descartes suggested a thought experiment of having no senses. ‘I will consider myself as having no hands, no eyes, no flesh, no blood, as not having a single sense’ (100). A more wilful form of forgetting the senses could hardly be imagined. Descartes looked to the hard inner core of certainty, pure reason, as a model applicable in all cases to the phenomena of the outside world.

The verb to forget is from the Old Teutonic getan‘to hold or to grasp’. Etymologically to forget is to lose one’s hold on something, to let it go. Descartes’ desire to actively forget was the catalyst for touch to be written out of the cultural history of the west. If to forget touch means it has lost its hold then it is important to call its history and meaning back into being.

We need to beckon to, to invite back, what we consigned to the background and to also allow our hands and feet to draw us into the world. Henri Focillon writes that:

Sight slips over the surface of the universe. The hand knows that an object has physical bulk that it is smooth or rough, that it is not soldered to heaven and earth from which it appears to be inseparable. The hand’s action defines the cavity of space and the fullness of the objects that occupy it. Surface, volume, density, and weight are not optical phenomena. Man first learned about them between his finger and the hollow of his palm. He does not measure space with his eyes but with his hands and feet. The sense of touch fills nature with mysterious forces. Without it nature is like the pleasant landscapes of the magic lantern slight, flat and chimerical (Focillon, p. 162-63).

Irigaray (1999) claims we have forgotten not only our senses but the air around us and in doing so we have also forgotten that we are nourished and supported by air. She argues that space is not empty but filled with the density of air that connects and separates everything on earth. Emotionally this sense of air enables us to experience space as thick with the flesh of the world and the texture of light (Vasseleu, 1998). One of the difficulties in these days of mask wearing and fear of contagion is that our sense of pleasure in air and light can be overwhelmed by anxiety. Those of us fortunate to have gardens are still able to explore the textured, resonant quality of the garden’s presence. I believe this is an experience essential to develop the ability to care for the natural world and I hope that garden writing can to some extent offset the sense of loss of the tangible world of flesh.

Merleau-Ponty uses the relationship of mother and infant as a model for nature’s presence and implicitly links it to a call for care. It is, he states, the mother’s idiom of care and the infant’s experience of this language of care that is the first human aesthetic. It is the most profound occasion where the content of the self is formed and transformed by the environment. The rapt attention, the absorption characterises this experience as aesthetic rather than cognitive. Eventually this aesthetic of handling yields to an aesthetic of language and the experience of being becomes integrated with the experience of thinking. Our positioning in nature is imbued by the rapport established in infancy. If this relationship has been ‘good enough’ nature can be experienced as an intimate collection of material sensations where dreams of who we are, of where we belong and of how we get on in life are consigned.

Writing about gardens is one way in which writer, text and reader can be re-positioned as palpably ‘of’ the world, oriented topologically and topographically ‘on’ and ‘in’ the world and surrounded by air thick with non-corporeal tactility. Garden writing can be a narrative that touches, that calls us to dwell within a nature full of mysterious forces that we can no more ignore than we can an infant’s cry in the night. It creates narratives that are open to healing the other within us and the other that is nature.

Such writing calls forth care. A call for care is defined by its direction, by its drift towards attachment. It is a desire to protect, to move towards as well as to hold and be held. The engagement that flows from and between both the bodies of writer and reader leads to a deepening or calling forth of new perceptions. This is not a relationship characterised by passivity on the one side and activity on the other. Instead, it is creative, mutual, reciprocated and actively constituted by both parties.

Although I believe this is the promise held out by garden writing there is no certainty that it can affect change. As Boch remarked, ‘a body that becomes hopeful inevitably holds the condition of defeat precarious within itself’ (Boch, 1998, p. 341). And language can never say all that can be said, but writing understood as flesh holds out the promise of aliveness and works against objectifying what it expresses. I imagine it like a tree trunk, a palimpsest of growing layers. Of spreading and branching joints of language, of sap rising and falling. As timber its rough rings release the song of the place, echoed in the timbre of voice laid down as inscriptions on porous paper, literally shapely words, lines curving like a cupped hand around space that appears empty yet reveals something, touched and held by translucent eyes and skin.

Bibliography

Boch, E. ‘Can Hope be Disappointed’? in Literary Studies. Stanford UP, 1998, pp.339-345.

Focillon, H. The Life of Forms in Art, trans. C. B. Hogan & G. Kubler, London, Zone, 1989.

Irigaray, Luce. The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger, trans Mary Beth Mader. London, Athlone, 1999.

Merle-Ponty, M. ‘The child’s relations with others,’ in The primacy of perception, ed. J. M. Edies. Evanston, Northwestern UP, 1989.

Vasseleu, Cathryn. Textures of Light: Visions and touch in Irigaray, Levinas and Mzerleau-Ponty. NY. Rutledge, 1998.

Beautiful! In thought and language.

LikeLike